So, the Pre-Cambrian cretins on the City of London’s Court

of Common Council have overruled their Pplanning & Transportation Committee’s

decision to support the closure of Tudor Street at its junction with New Bridge

Street.

The decision apparently follows fierce lobbying by senior figures

in the Inner Temple, including Baroness Butler-Sloss. Their logic? Apparently it interferes with deliveries to

Temple and would prevent film crews accessing the area for filming, which would

deprive the Temple of some revenues.

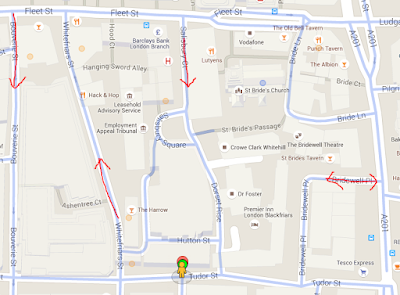

So, what access, apart from the eastern end, is available to

vehicles wishing to go to or deliver in Tudor Street?

Well, you can enter from

Fleet Street via Salisbury Court or Bouverie Street, and you can exit to Fleet

Street via Whitefriars Street. It is

planned that you can enter or exit to New Bridge Street via Bridewell Place,

and you can exit to New Bridge Street via Watergate, which brings you out next

to the Unilever Building. Not exactly no choice!

|

| Left-turn lane for New Bridge St traffic to turn into Bridewell Place. To permit turning into Tudor St TfL would need to provide a similar lane there, and there isn't room there. |

|

| The cycle lane just north of Bridewell Place. Note the eye-level traffic signal - this junction has always been light-controlled. The Tudor St/New Bridge St junction never has been. |

The streets to the south, towards Embankment, are largely

filtered now and I understand that TfL wants Temple Avenue to be filtered too.

How do these access points work out, for large commercial

vehicles – you know, like film crew trucks?

|

| There is actually ample space for two HGVs to pass each other here - or there would be. |

Yes, parking bays and a taxi stand already constrict access

fairly tightly, as this photo I took this lunchtime demonstrates – the eastbound

HGV mounting the pavement to make space for a westbound HGV to pass through the

narrow gap. I didn’t photograph it, but I also noted that in Whitefriars Street

the no parking, no loading “At Any Time” markings were being constantly and

routinely flouted, further obstructing the passage of vehicles.

And when a large vehicle – you know, a film crew’s truck –

gets to the end of Tudor Street where the gate into Temple can be found? Well, this is what they will find.

|

| The sign says "Vehicle Restrictions: 3.4m high, 2.4m wide" Large enough for a film truck, say? |

A bit like the Needle’s Eye in Jerusalem which apparently

gave us the famous Biblical quote about camels.

So what is the fuss really about? Yes, this:

|

| And in case you couldn't read that sign... |

Yes, there may be some notable senior QCs who have not yet

lost the use of their legs, but apparently not many.